What do scholarly journal pieces on marketing, business books and great 20th century novels have in common? They are written, and then read, in specific moments of time. Those moments affect the works’ impact on readers as much as or more than their content alone.

What do scholarly journal pieces on marketing, business books and great 20th century novels have in common? They are written, and then read, in specific moments of time. Those moments affect the works’ impact on readers as much as or more than their content alone.

When my kids were in high school, I enjoyed reading – re-reading, actually – many of the books they were assigned. The immediate goal was an attempt to help deepen their engagement with the work and provide whatever illumination I could from a perspective that might be different from their teachers and peers. It sure didn’t seem like work or parental obligation to me. It was not only fun and rewarding to talk to my children about great literature, it was also a wonderful excuse to revisit these works. Surprises were always in store. The plot points, imagery, brilliant language, subtle humor and more that I missed as a teenager jumped out at me as more mature reader.

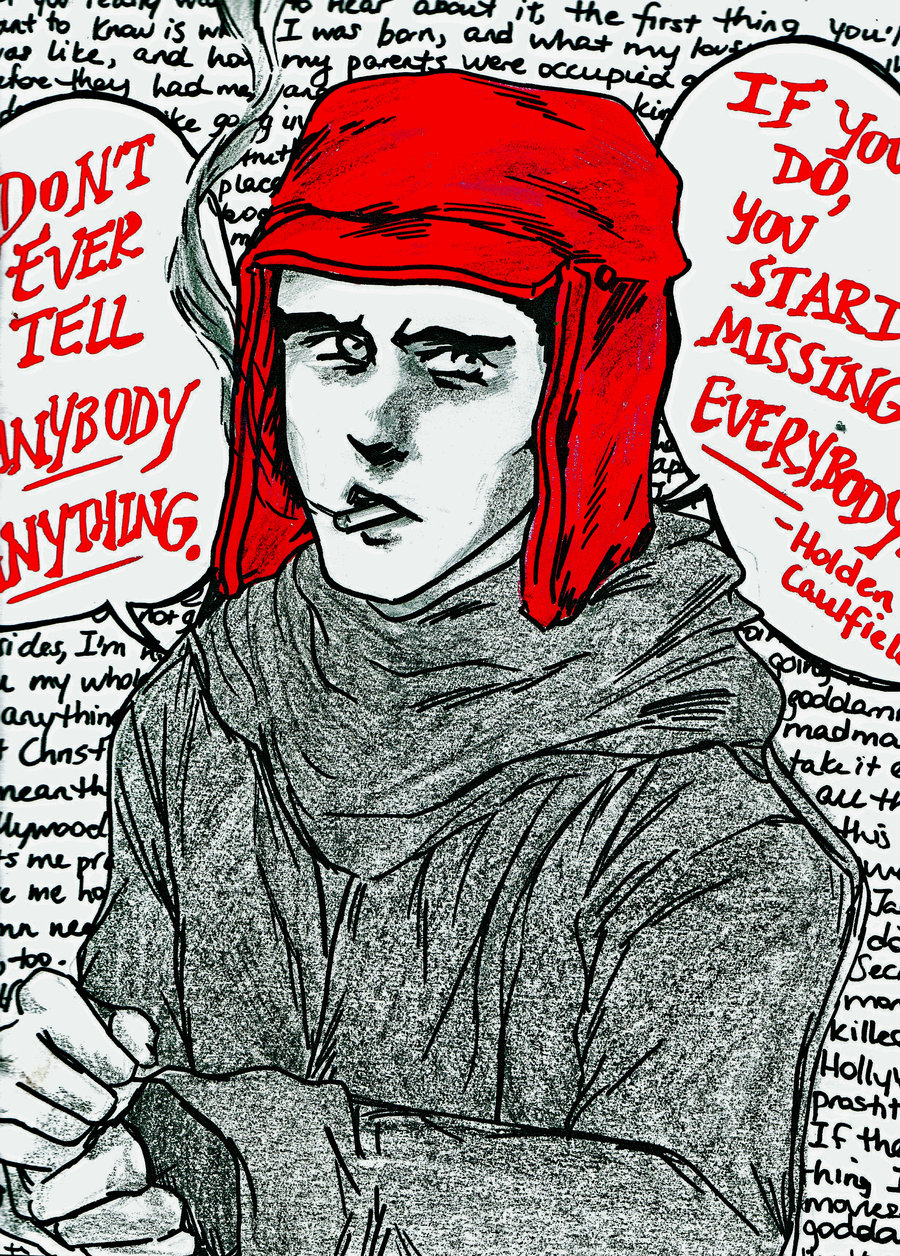

I was most astonished by my reactions to “The Catcher in the Rye.” As a ninth grader, I remember so closely identifying with Holden Caulfield, J.D. Salinger’s alienated teenage protagonist. I felt his pain, his insecurities, his struggles to fit in. But as an adult and father of three teenagers at the time, reading about Holden’s adventures made me think, “What an immature jerk. This kid needs to quit whining and get a life.

Another eye-opening experience in changing perspectives is now unfolding for me at USC, where I’ve had the privilege of lecturing recently, as well as participating in Dr. Ben Lee’s graduate class on branding. Dr. Lee assigned three books to his students along with numerous articles from the mainstream press and academic journals. (I’ve already posted a piece on one of these books, the excellent “Different” by Harvard Business School’s Youngme Moon, which you can read here.)

What is so striking to me is how differently I take in the content as an experienced marketer as opposed to a young student. Just as I once identified with Holden, I accepted every reading in graduate school as a certain fact. Whatever it said in Doug Kotler’s textbook – and of course those written by my own professors that were required reading – must be true beyond the shadow of a doubt.

Now I read these instructional marketing materials with a great deal of skepticism. One author states authoritatively, with absolutely no evidence to support his premise, that there are “5 types of brands” and 6 strata in the “spectrum of brand promises.”

Really? That doesn’t mesh with my experience as a strategist, and it probably doesn’t fit yours either. But if you’re a young student, even if you’re quite brilliant, you’re likely to take it on faith. What else do you have to compare it to?

Still, I understand the impulse of this author and others. Marketers, in our efforts to make sense of complex and often contradictory data and cues, love to sort into “buckets.” Marketing professionals and writers brim with confidence as they tell you “the six essential things you need to know about positioning” or “the five ways to break through on social media.” From the reader’s perspective, this paint-by-numbers approach is easily digestible. But it’s dangerous.

There is an expression I love to use when thinking about some of my more left-brained colleagues. “They know how the watch works but they can’t tell time.”

Not only do they miss the big picture issues, zeroing in on a rational and often meaningless feature rather than understanding the true, emotional benefit of the brand, but they put their faith in process over substance. I see this most often in old-line packaged goods companies to the point where the development of a distinct brand positioning and personality are virtually ignored, subjugated to a soulless and ultimately, non-proprietary “product claim.”

Marketers of all ages need to be skeptics. I am all for process – we certainly have our own way of working in my company – but there needs to be room for constant questioning, rigorous challenge and debate. Great ideas are born out of curiosity, not rigid adherence.

I certainly got a lot more from all of my recent business reading from this perspective. While I question anyone’s ability to quantify something like a “spectrum of brand promises,” I’d like to think that these business writers are doing this simply to put stakes in the ground, giving us organizing principles, not rigid rules, to help us start thinking about marketing problems. They are giving us a context in which to create, develop and challenge ideas. It’s a much more productive approach as compared to what I would have done as a student, which would have been to learn those 5 types of brands by rote and before attempting to pigeon hole every existing (and future) product into one of those slots.

If you’re mining for gold when reading business books, employing some marketing model or relying on a deeply imbedded process, don’t expect to get rich quick. The experts can help us tee up the issues but they won’t give us the answers. Instead, pan for the nuggets of insight that will help build a wealth of knowledge and know-how over time. And when you find one of those nuggets, make sure you vet it completely to make sure you’re not going to the bank with fool’s gold.

Most important, this notion of context and perspective must be kept in mind when considering how biased all of us are, despite our best intentions. Some combination of nature and nurture leads us to very specific conclusions that from a marketing perspective will affect our judgment. Whether you are a twenty-something marketer working on luxury products for senior citizens or a fifty-something who needs to evaluate social media plans for a new app, your personal circumstances will interfere with your ability to make sound decisions.

Holden will always be a hero to some and a twit to others. It just depends, right? And it’s why marketing is more art than science. Everything is subjective and always changing, a never ending adventure. It’s why we do what we do.