On a recent shopping excursion to Beverly Hill’s Rodeo Drive, I visited What Comes Around Goes Around, an industry renown, high-end secondhand store known as the “leading purveyor of authentic luxury and vintage pieces.”

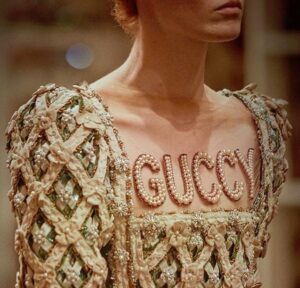

Meandering through the carefully curated racks, I immediately noticed that ubiquitous “Gucci” logo adorned by every celebrity and social media influencer in 2017. Except this was an obvious knock-off screen printed on a Jerzees wholesale sweater for $550.

(Yes, it’s a counterfeit, but it’s vintage and that’s the pricing difference between flea market vintage and “curated” vintage—But that’s another blog in itself! Yet $550 can still be considered a “deal” as the authentic version will run you about $1,300 on Gucci.com!)

So how did knock-offs become influential, highly coveted and trendy?

Gucci became “Guccy” for its 2018 Cruise collection.

Dolce & Gabbana released a leather, crystal and stud-embellished pouch boldly emblazed “This is a D&G Fake Bag” at a luxe price point of $2,195.

Though still rather exclusive, the fashion world has loosened up a bit from its highfalutin image.

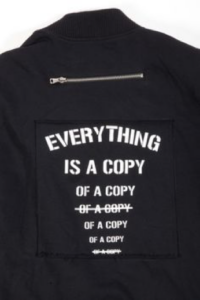

When an entire industry is built upon commodifying rarity and superiority, poking fun of oneself and finding inspiration through sketchy Chinatown counterfeits is quite paradoxical.

But does this come with a price? (More on that later.) This perplexed sense of humor, along with big splashy logos and loud modern designs can partly be attributed to a more prevalent than ever, blurred line between high and low, streetwear and luxury. The ambiguity is strong; popular streetwear blog High Snobiety even published a recent feature brashly titled It’s Official: Streetwear and Luxury are Now the Same Thing.

Then there’s the insider, shared sentiment among the fashion elite: An entirely designer wardrobe is snotty and usually a sign of bad taste. Fashion consultant/TV personality Tim Gunn believes the problem with too much money is you lose creativity; you buy what you think you’re supposed wear as opposed to developing your own personal style. The late legendary designer Alexander McQueen famously said, “I think the idea of mixing luxury and mass-market fashion is very modern, very now—No one wears head to toe designer anymore.” Angelina Jolie has even donned a $26 dress from vintage Melrose Avenue retailer Wasteland along with $700 Louboutin heels to her premiere of A Mighty Heart more than a decade ago. Mixing high and low was in and never left.

High and low culture is tightly intertwined. Youth and grassroots culture has historically influenced high-brow fashion, but never to the extent seen in the age of social. For instance, the success of the Gucci x Trouble Andrew collaboration stemmed directly from Gucci Creative Director Alessandro Michele’s fascination with the Internet and the streets.

Michele embraced memes, street style, social media and political statements in unconventional ways, which bolstered the brand’s relevance, virality and proved “Gucci does the most” and that “Maximalism had no expiration date.” (Since appointed in 2015, Michele has been credited for the Italian fashion house’s exponential growth, as sales grew 49%, equivalent to $1.82 billion, in the third quarter fiscal of 2017.)

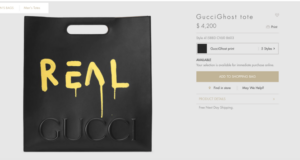

Trevor “Trouble” Andrew was a former professional skater and Olympic snowboarder turned Brooklyn musician/street artist. A self-professed Gucci junkie, he purchased his first Gucci watch more than two decades ago, at 17, from money he won competing.

His moniker GucciGhost was born in 2013, when Andrew, desperate for a last-minute Halloween costume, decided to cut holes in his Gucci bedsheets and while out and about in New York, passerbys would exclaim “Gucci Ghost!” The name stuck, and he started spraying his interpretation of the Gucci logo throughout the city, Instagramming the images and using the hashtag #GucciGhost, which gained him further Internet notoriety. A couple years later, Andrew receives a call from Michele where he invites him to Milan to partner for the Fall Winter 2016 line.

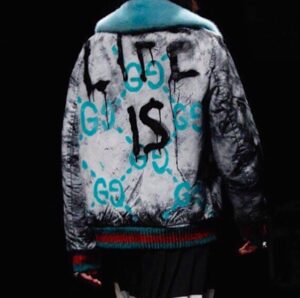

Daniel “Dapper Dan” Day was a couturier who ran a Harlem boutique in the 80’s. His work was a juxtaposition of “high” and low, he would mix and stitch iconic replica luxury logos and patterns (Fendi, Louis Vuitton, Gucci) with smaller independent labels to produce his own idiosyncratic designs.

He was revered as the go-to-best-kept-Harlem-secret during hip-hop’s “golden-era” (Mike Tyson, Salt-n-Peppa, LL Cool J) where rappers and athletes would flock to his store to commission unconventional, custom-made designs.

Luxury brands, including Gucci, eventually caught wind and multiple lawsuits caused him to close shop in 1992.

Today he’s more relevant than ever: A full circle moment in 2016 emerged when Michele paid homage to Dapper Dan by knocking off his knockoff, an 80s-fur jacket with Louis Vuitton motif puff sleeves—though now on the spring/summer 2018 resort collection runway with Gucci’s G—originally constructed for Olympian runner Diane Dixon in 1989.

Dapper Dan is revered by the Museum of Modern Art’s senior curator of architecture and design Paola Antonelli, who will include his pieces in an upcoming exhibit. In a New York Times interview, Antonelli refers to Dapper Dan as a “trailblazer” who “showed even the guardians of the original brands the power of creative appropriation, the new life that an authentically ‘illicit’ use could inject into a stale logo, as well as the commercial potential of a stodgy monogram’s walk on the hip-hop side.”

In a traditional legal sense, Dapper Dan stole trademarked work and broke the law. Today he is considered an innovator and celebrated for his original twists on iconic logos that have historically represented elitism.

Gucci has since partnered with Dapper Dan through campaigns, a capsule collection and will, in a twist of irony, sponsor the reopening of his brick-and-mortar, by-appointment-only atelier 2.0. According to a statement released from Gucci, the project is quite the dichotomy “Made in Italy meets Made in Harlem and the 1980s meets 2018.”

The ambiguity of “authenticity” leaves questions to be pondered:

What does that mean for the future of copyright infringement and intellectual property? Louis Vuitton issued streetwear brand Supreme a cease & desist in 2000, when they were a young independent New York skate brand. Yet last year, the Louis Vuitton x Supreme partnership made headlines as soon as the collection made its runway debut at Le Palais Royale and to date, has been one of the most successful collaborations in the label’s history: The release immediately sold-out and resale prices skyrocketed. (7,500 fashion enthusiasts queried in Tokyo alone!)

Dazed fashion editor Emma Hope Allwood lends her two cents, “I think the pieces which incorporate the monogram with the Supreme logo are the strongest—They remind me of the kind of bootlegs you might find in a dodgy Asian marketplace or on Ava Nirui’s Instagram feed. It’s another take on the official fake (like those wildly popular Gucci cruise T-shirts); a trend which calls into question ideas of authenticity and originality, both of which are concepts that are central to Supreme and Vuitton as brands.”

Will high fashion’s whirlwind upside-down, inside-out, love/hate relationship with bootlegging create consumer confusion and what are the long-term repercussions?

(The global counterfeit market accounts for 10% of losses annually and is estimated to be worth $450 billion, while stealing sales and diluting brand reputation.)

Will Gucci to “Guccy” lessen the stigma and condition shoppers to view counterfeit goods as socially acceptable? I mean, it’s already difficult for the average consumer to distinguish counterfeits from the real thing as is. In fact, some replicas have gotten so good that even industry professionals are stumped.

Are Dapper Dan 80s vintage counterfeits and Trouble Andrew “Gucci” paintings, before the partnerships, now “authentic?” What constitutes authenticity? Must it require a stamp of licensing approval from the House? One can even argue that uppity heritage brands, desperate to revamp a pervasive and sterile logo, appropriate and profit off urban culture for relevancy. From a sociological perspective, is this black appropriation or tribute/homage? And where are the lines drawn?

There are no easy answers, where the runway meets the streets is a complicated intersection–Proceed with caution.

Update:

Capitalizing off the luxury counterfeit trend, mid-market label Diesel announced today that they’re opening up their own “official knock-off” pop-up on Canal Street, misspelled “Deisel.” Rapper Gucci Mane is stated to make an official launch appearance, and limited edition apparel from the capsule collection, to be sold at affordable knock-off prices, will be placed in red boxes that look awfully similar to Supreme. Lines quickly formed when word got out, and resellers have already started flipping “Deisel” on eBay for profit!