Minimalism is omnipresent and its meaning has evolved.

The term has been thrown around loosely, used to describe everything from an industrial-style, artisanal cafe with natural, exposed brick, luminous whitest of white walls and green succulents to a let-me-put-in-effort-to-look-effortless “capsule wardrobe,” comprised of quality monochrome basics.

This “less is more” state also describes the lives of many cosmopolitan Millennials. They shun vehicle ownership in favor of Lyft/Uber and seek nomadic, “micro homes” for their low maintenance, sustainability and the freedom to travel on a whim.

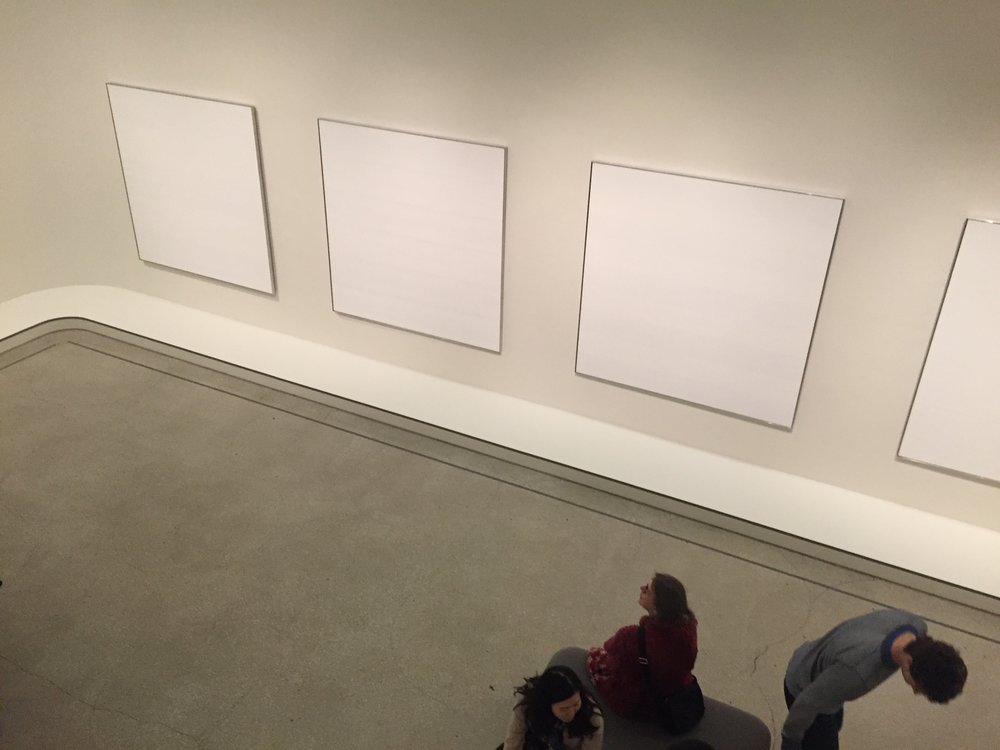

Previously, the generally accepted mainstream definition of minimalism dates to 1965, when British philosopher Richard Wollheim described artists whose work simply lacked—such as a sliver of dripped paint on a blank canvas or a pile of denim haphazardly laid on a gallery floor. Whether he believed the work was aesthetically ill-favored or bereft of refined dexterity, Wollheim cast these artists as incompetent egoists whose works were unworthy of acclaim.

How things change. Today, as demonstrated by Millennials and other cosmopolitan elites, minimalism is no longer a form of mockery used to antagonize a form of highbrow art.

We can look at minimalism from the perspectives of aesthetics and philosophy.

Aesthetically, a minimalist home is comprised of clean lines, is free of clutter and comes off as sterile and utilitarian.

From a branding perspective, Apple is the pioneer of minimalist design.

Philosophically, minimalism is about reassessing priorities and ridding excess, whether that is material goods, relationships or ideas that do not add value to life.

Several societal factors seem to contribute to minimalism’s modern-day appeal:

- Our more-complicated-than-ever-before, tech-fatigue culture of constant dings and rings has given rise to industries capitalizing on “simplicity” and “decluttering the mind.” Examples include meditation, pure ingredients and possession purges.

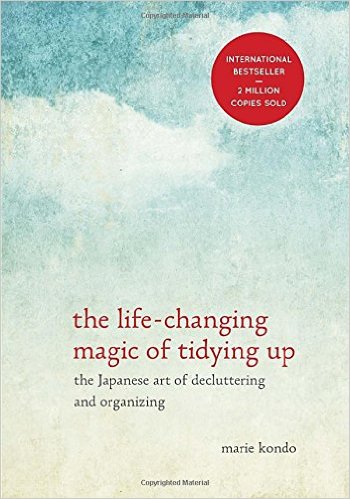

The desire for clarity continues to grow: Author and consultant Marie Kondo was listed as one of Time’s “100 Most Influential People” and shot to international acclaim due to the enormous receptiveness of her book The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing. As to date, her work has accumulated more than 12 thousand positive reviews on Amazon.

2. There is an entire generation that needs to make more from less. The increase in urban dwelling has driven up rent at the same time when young people are dealing with a less than robust job market. Skyrocketing student loans don’t help. These conditions have rendered “keeping up with the Jones’” a thing of the past.

3. We are living in a more globally conscious culture with social awareness for environmental initiatives and sustainability is at an all-time high. Minimalism, philosophically, is about making the most of less. (Example: co-workspace.)

4. Social media paved the way for a hyper-curated culture. Pinterest and Instagram made minimalism aesthetically pleasing and do-able for the average person. In our culture of overconsumption, it’s much easier to decorate with less. Idiosyncratic spaces require time, detail and a natural inventiveness that can take years of refining.

The less is more craze has propelled new startups embracing minimalist ideals. Serial entrepreneurs Ido Leffler and Tina Sharkey founded Brandless, an it’s-not-a-brand brand that has quickly gained a loyal following and to date, raised more than 50 million dollars in funding. They are an online, direct-to-consumer company that sells basic consumer packaged goods for $3. Brandless prides themselves on cutting out the middleman, such as traditional brick-and-mortar distribution, to keep quality high and prices low. The Brandless mission is “deeply rooted in quality, transparency and community-driven values. Better stuff, fewer dollars. It’s that simple.”

The minimalism movement has aided in the rapid U.S. expansion of Muji – meaning no-brand quality goods in Japanese – a lifestyle store with a wide range of generic products including apparel, stationary, travel and home goods. This no-brand brand “embraces the feelings and thoughts of all people” by incorporating three core principles into their mission:

-

- Selection of processes;

- Streamlining of processes; and,

- Simplification of package

A press release distributed recently announced that the brand, particularly at the Tokyo flagship location, will now sell local, organic fruits and vegetables and shoppers will be able to read personal notes from farmers while picking produce. This idea falls into minimalist principles, emphasizing small rather than corporate farming. To step it up a notch, a real life “tiny house” is displayed in the store and interior designers are on hand to answer questions about minimalist design ideology. Moreover, Muji is opening hotels in urban hotspots of Tokyo and Shenzhen as another avenue for consumers to fully experience the “Muji” lifestyle. U.S. hospitality expansion may not be far off.

“Going minimalist” has helped once-struggling youth apparel retailer Urban Outfitters turn around flagging sales. Inventory management through lean stock resulted in fewer markdowns (ZARA’s successful model) and a push towards basic, simplistic styles a la 90’s minimalist nostalgia (Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, Wrangler) and casual versatility has kept the brand culturally relevant.

In addition, the brand introduced Rework, its own minimalist collection “made from limited runs of remnant fabrics,” along with Urban Renewal, an eco-friendly, upcycled vintage line. By doing so, it might seem that Urban Outfitters is rebelling against retail’s fast fashion epidemic. (Yes critics would argue that they are participants in the fast-fashion arms race themselves but the point is, Urban Outfitters carries the perception of sustainability through minimalism, which has revived business.)

So what does this mean for brands? And does the minimalism trend have staying power?

Modern critics of minimalism echo those from several generations back. They argue that minimalism is a faux rationale embraced by the privileged as a means of making sense of their rose-colored world and a new avenue to feel holier-than-thou. For example, it’s not difficult to eradicate an entire wardrobe and strip down to the basics when one has the means to easily obtain it back. Eating clean can be pricey and an entirely white living space may not be practical for most. In a New York Times piece dubbed “The Oppressive Gospel of Minimalism,” David Raskin, a contemporary art history professor at the School of the Art Institute Chicago explains, “One of the real problems with design-world minimalism is that it’s just become a signifier of the global elite—The richer you are, the less you have.”

From a design perspective, trends come and go. Modern-style exterior/interior—another concept of minimalism—can be loathsome to those who crave visual stimulation. It can also be too confining to someone who, for example, enjoys a home with “charm” and “personality,” that tells a unique story about the person inhabiting the space.

There is a push for “less is more” but the conflicting message is “more is more, less is a bore.” Bright colors! Clashing patterns! Ornate styles! Scroll through any popular design blog and you’ll see something along the lines of, “Vibrant Spaces: Maximalism is in!” or “Minimalism is Dead, Hello Maximalism!” Look in the rearview mirror and you’ll see audacity slowly but surely creeping its way behind simplicity and its paving its own glitter-embellished lane.

However, from an ideological standpoint, a big yes: Minimalism will stay. Values, such as caring about the environment by purchasing ethically-produced clothing for example, are deeply ingrained in the psych and last. Logical or otherwise, values are cemented and motivating. They are the essence of a person’s identity.

And perhaps the best brand you can wear is your own identity.